In multimedia, the quality engineers are optimizing for is perceptual. Eyes, ears, and the brain processing their signals are enormously complex, and there’s no way to replicate everything computationally. There are no “objective” metrics to be had, just various proxies with difficult tradeoffs. Modifying video is particularly thorny, since like I’ve mentioned before on this blog there are various ways to subtly bias perception that are nonetheless undesirable, and are impossible to correct for.

This means there’s no substitute for actually looking at the results. If you are a video engineer, you must look at sample output and ask yourself if you like what you see. You should do this regularly, but especially if you’re considering changing anything, and even more so if ML is anywhere in your pipeline. You cannot simply point at metrics and say “LGTM”! In this particular domain, if the metrics and skilled human judgement are in conflict, the metrics are usually wrong.

Netflix wrote a post on their engineering blog about a “deep downscaler” for video, and unfortunately it’s rife with issues. I originally saw the post due to someone citing it, and was incredibly disappointed when I clicked through and read it. Hopefully this post offers a counter to that!

I’ll walk through the details below, but they’re ultimately all irrelevant; the single image comparison Netflix posted looks like this (please ‘right-click -> open image in new tab’ so you can see the full image and avoid any browser resampling):

Note the ringing, bizarre color shift, and seemingly fake “detail”. If the above image is their best example, this should not have shipped – the results look awful, regardless of the metrics. The blog post not acknowledging this is embarrassing, and it makes me wonder how many engineers read this and decided not to say anything.

The Post

Okay, going through this section by section:

How can neural networks fit into Netflix video encoding?

There are, roughly speaking, two steps to encode a video in our pipeline:

1. Video preprocessing, which encompasses any transformation applied to the high-quality source video prior to encoding. Video downscaling is the most pertinent example herein, which tailors our encoding to screen resolutions of different devices and optimizes picture quality under varying network conditions. With video downscaling, multiple resolutions of a source video are produced. For example, a 4K source video will be downscaled to 1080p, 720p, 540p and so on. This is typically done by a conventional resampling filter, like Lanczos.

Ignoring the awful writing1, it’s curious that they don’t clarify what Netflix was using previously. Is Lanczos an example, or the current best option2? This matters because one would hope they establish a baseline to later compare the results against, and that baseline should be the best reasonable existing option.

2. Video encoding using a conventional video codec, like AV1. Encoding drastically reduces the amount of video data that needs to be streamed to your device, by leveraging spatial and temporal redundancies that exist in a video.

I once again wonder why they mention AV1, since in this case I know it’s not what the majority of Netflix’s catalog is delivered as; they definitely care about hardware decoder support. Also, this distinction between preprocessing and encoding isn’t nearly as clean as this last sentence implies, since these codecs are lossy, and in a way that is aware of the realities of perceptual quality.

We identified that we can leverage neural networks (NN) to improve Netflix video quality, by replacing conventional video downscaling with a neural network-based one. This approach, which we dub “deep downscaler,” has a few key advantages:

I’m sure that since they’re calling it a deep downscaler, it’s actually going to use deep learning, right?

1. A learned approach for downscaling can improve video quality and be tailored to Netflix content.

Putting aside my dislike of the phrase “a learned approach” here, I’m very skeptical of “tailored to Netflix content” claim. Netflix’s catalog is pretty broad, and video encoding has seen numerous attempts at content-based specialization that turned out to be worse than focusing on improving things generically and adding tuning knobs. The encoder that arguably most punched above its weight class, x264, was mostly developed on Touhou footage.

2. It can be integrated as a drop-in solution, i.e., we do not need any other changes on the Netflix encoding side or the client device side. Millions of devices that support Netflix streaming automatically benefit from this solution.

Take note of this for later: Netflix has many different clients and this assumes no changes to them.

3. A distinct, NN-based, video processing block can evolve independently, be used beyond video downscaling and be combined with different codecs.

Of course, we believe in the transformative potential of NN throughout video applications, beyond video downscaling. While conventional video codecs remain prevalent, NN-based video encoding tools are flourishing and closing the performance gap in terms of compression efficiency. The deep downscaler is our pragmatic approach to improving video quality with neural networks.

“Closing the performance gap” is a rather optimistic framing of that, but I’ll save this for another post.

Our approach to NN-based video downscaling

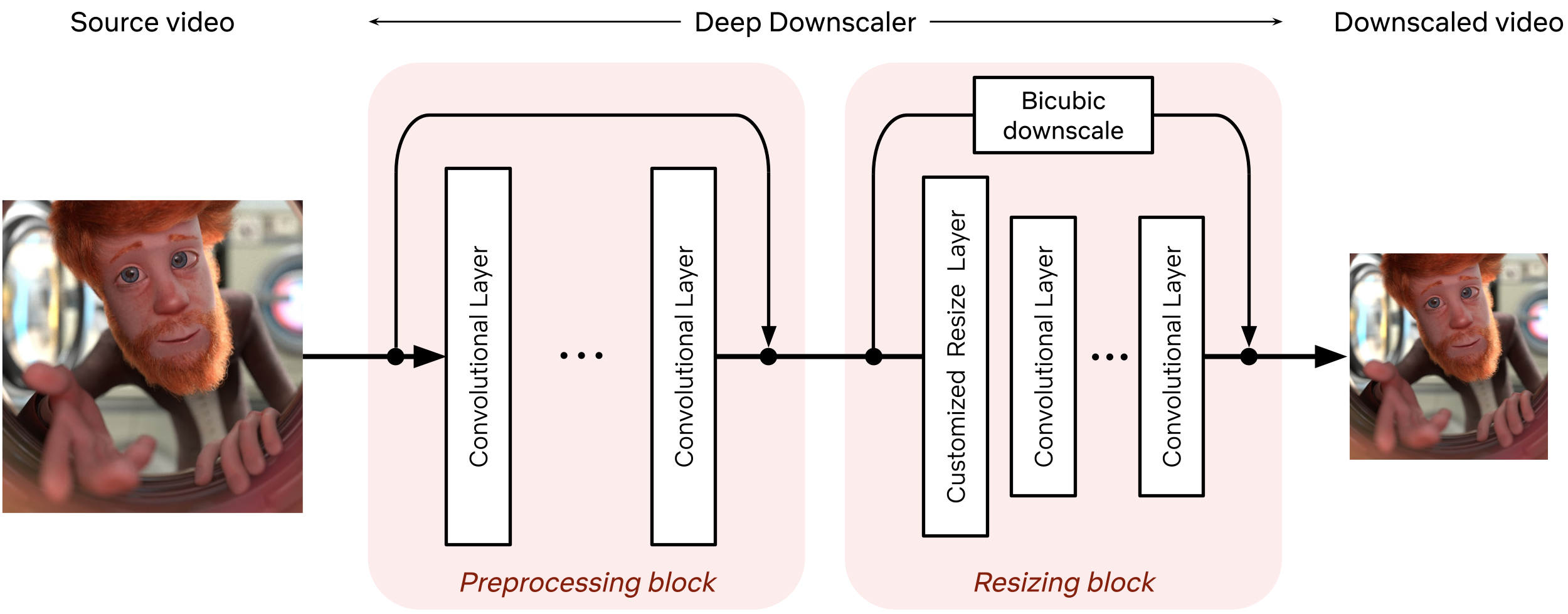

The deep downscaler is a neural network architecture designed to improve the end-to-end video quality by learning a higher-quality video downscaler. It consists of two building blocks, a preprocessing block and a resizing block. The preprocessing block aims to prefilter the video signal prior to the subsequent resizing operation. The resizing block yields the lower-resolution video signal that serves as input to an encoder. We employed an adaptive network design that is applicable to the wide variety of resolutions we use for encoding.

I’m not sure exactly what they mean by the adaptive network design here. A friend has suggested that maybe this just means fixed weights on the preprocessing block? I am, however, extremely skeptical of their claim that the results will generate to a wide variety of resolutions. Avoiding overfitting here would be fairly challenging, and there’s nothing in the post that inspires confidence they managed to overcome those difficulties. They hand-wave this away, but it seems critical to the entire project.

During training, our goal is to generate the best downsampled representation such that, after upscaling, the mean squared error is minimized. Since we cannot directly optimize for a conventional video codec, which is non-differentiable, we exclude the effect of lossy compression in the loop. We focus on a robust downscaler that is trained given a conventional upscaler, like bicubic. Our training approach is intuitive and results in a downscaler that is not tied to a specific encoder or encoding implementation. Nevertheless, it requires a thorough evaluation to demonstrate its potential for broad use for Netflix encoding.

Finally some details! I was curious how they’d solve the lack of a reference when training a downscaling model, and this sort of explains it; they optimized for PSNR when upscaled back to the original resolution, post-downscaling. My immediate thoughts upon reading this:

- Hrm, PSNR isn’t great3.

- Which bicubic are we actually talking about? This is not filling me with confidence that the author knows much about video.

- So this is like an autoencoder, but with the decoder replaced with bicubic upscaling?

- Doesn’t that mean the second your TV decides to upscale with bilinear this all falls apart?

- Does Netflix actually reliably control the upscaling method on client devices4? They went out of their way to specify earlier that the project assumed no changes to the clients, after all!

- I wouldn’t call this intuitive. To be honest, it sounds kind of dumb and brittle.

- Not tying this to a particular encoder is sensible, but their differentiability reason makes no sense.

The weirdest part here is the problem formulated in this way actually has a closed-form solution, and I bet it’s a lot faster to run than a neural net! ML is potentially good in more ambiguous scenarios, but here you’ve simplified things to the point that you can just do some math and write some code instead5!

Improving Netflix video quality with neural networks

The goal of the deep downscaler is to improve the end-to-end video quality for the Netflix member. Through our experimentation, involving objective measurements and subjective visual tests, we found that the deep downscaler improves quality across various conventional video codecs and encoding configurations.

Judging from the example at the start, the subjective visual tests were conducted by the dumb and blind.

For example, for VP9 encoding and assuming a bicubic upscaler, we measured an average VMAF Bjøntegaard-Delta (BD) rate gain of ~5.4% over the traditional Lanczos downscaling. We have also measured a ~4.4% BD rate gain for VMAF-NEG. We showcase an example result from one of our Netflix titles below. The deep downscaler (red points) delivered higher VMAF at similar bitrate or yielded comparable VMAF scores at a lower bitrate.

Again, what’s the actual upscaling filter being used? And while I’m glad the VMAF is good, the result looks terrible! This means the VMAF is wrong. But also, the whole reason they’re following up with VMAF is because PSNR is not great and everyone knows it; it’s just convenient to calculate. Finally, how does VP9 come into play here? I’m assuming they’re encoding the downscaled video before upscaling, but the details matter a lot.

Besides objective measurements, we also conducted human subject studies to validate the visual improvements of the deep downscaler. In our preference-based visual tests, we found that the deep downscaler was preferred by ~77% of test subjects, across a wide range of encoding recipes and upscaling algorithms. Subjects reported a better detail preservation and sharper visual look. A visual example is shown below. [note: example is the one from above]

And wow, coincidentally, fake detail and oversharpening are common destructive behaviors from ML-based filtering that unsophisticated users will “prefer” despite making the video worse. If this is the bar, just run Warpsharp on everything and call it a day6; I’m confident you’ll get a majority of people to say it looks better.

This example also doesn’t mention what resolution the video was downscaled to, so it’s not clear if this is even representative of actual use-cases. Once again, there are no real details about how the tests with conducted, so I have no way to judge whether the experiment structure made sense.

We also performed A/B testing to understand the overall streaming impact of the deep downscaler, and detect any device playback issues. Our A/B tests showed QoE improvements without any adverse streaming impact. This shows the benefit of deploying the deep downscaler for all devices streaming Netflix, without playback risks or quality degradation for our members.

Translating out the jargon, this means they didn’t have a large negative effect on compressability. This is unsurprising.

How do we apply neural networks at scale efficiently?

Given our scale, applying neural networks can lead to a significant increase in encoding costs. In order to have a viable solution, we took several steps to improve efficiency.

Yes, which is why the closed-form solution almost certainly is faster.

The neural network architecture was designed to be computationally efficient and also avoid any negative visual quality impact. For example, we found that just a few neural network layers were sufficient for our needs. To reduce the input channels even further, we only apply NN-based scaling on luma and scale chroma with a standard Lanczos filter.

OK cool, so it’s not actually deep. Why should words have meaning, after all? Only needing a couple layers is not too shocking when, again, there’s a closed-form solution available.

Also, while applying this to only the luma is potentially a nice idea, if it’s shifting the brightness around you can get very weird results. I imagine this is what causes the ‘fake detail’ in the example above.

We implemented the deep downscaler as an FFmpeg-based filter that runs together with other video transformations, like pixel format conversions. Our filter can run on both CPU and GPU. On a CPU, we leveraged oneDnn to further reduce latency.

OK sure, everything there runs on FFmpeg so why not this too.

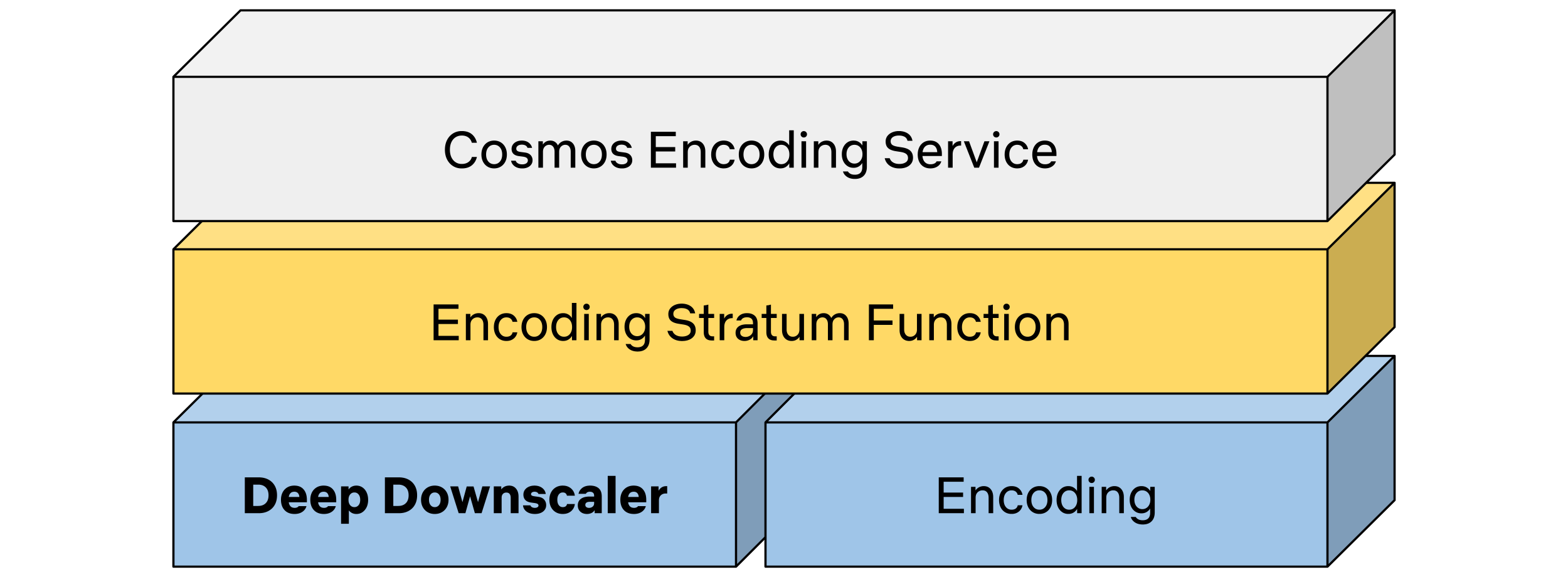

Integrating neural networks into our next-generation encoding platform

The Encoding Technologies and Media Cloud Engineering teams at Netflix have jointly innovated to bring Cosmos, our next-generation encoding platform, to life. Our deep downscaler effort was an excellent opportunity to showcase how Cosmos can drive future media innovation at Netflix. The following diagram shows a top-down view of how the deep downscaler was integrated within a Cosmos encoding microservice.

Buzzword buzzword buzzword buzzword buzzword. I especially hate “encoding stratum function”.

A Cosmos encoding microservice can serve multiple encoding workflows. For example, a service can be called to perform complexity analysis for a high-quality input video, or generate encodes meant for the actual Netflix streaming. Within a service, a Stratum function is a serverless layer dedicated to running stateless and computationally-intensive functions. Within a Stratum function invocation, our deep downscaler is applied prior to encoding. Fueled by Cosmos, we can leverage the underlying Titus infrastructure and run the deep downscaler on all our multi-CPU/GPU environments at scale.

Why is this entire section here? This should all have been deleted. Also, once again, buzzword buzzword buzzword buzzword buzzword.

What lies ahead

The deep downscaler paves the path for more NN applications for video encoding at Netflix. But our journey is not finished yet and we strive to improve and innovate. For example, we are studying a few other use cases, such as video denoising. We are also looking at more efficient solutions to applying neural networks at scale. We are interested in how NN-based tools can shine as part of next-generation codecs. At the end of the day, we are passionate about using new technologies to improve Netflix video quality. For your eyes only!

I’m not sure a downscaler that takes a problem with a closed-form solution and produces terrible results paves the way for much of anything except more buzzword spam. I look forward to seeing what they will come up with for denoising!

Thanks to Roger Clark and Will Overman for reading a draft of this post. Errors are of course my own.

-

1: Okay, I can’t help myself but at least I confined it to a footnote. That second sentence is awful writing, and even more bizarre is the third and fourth ones following it, which read like they were written by an entirely different person. I suspect this post went through too many rounds of edits and along the way no one sat back and gave the whole thing a clean read. ↩

-

2: It’s not. ↩

-

3: PSNR is an error metric that doesn’t take into account the quirks of human perception at all. It’s easy to compute, and “objective”, but unfortunately human brains are weird. ↩

-

4: I’m very, very doubtful. ↩

-

5: Of course, I suspect doing this would reveal that the results are not actually very good. ↩

-

6: One day someone is going to take me seriously when I joke about this and I’m going to regret everything. ↩